By Terry W. Johnson

One of the many reasons why I enjoy winter bird feeding is that it is full of surprises. During this time of the year, permanent residents such as cardinals and chipping sparrows feed alongside winter migrants like pine siskins, purple finches, white-throated sparrows and dark-eyed juncos. And from time to time, some of the luckiest among us even host a rare winter hummingbird or two.

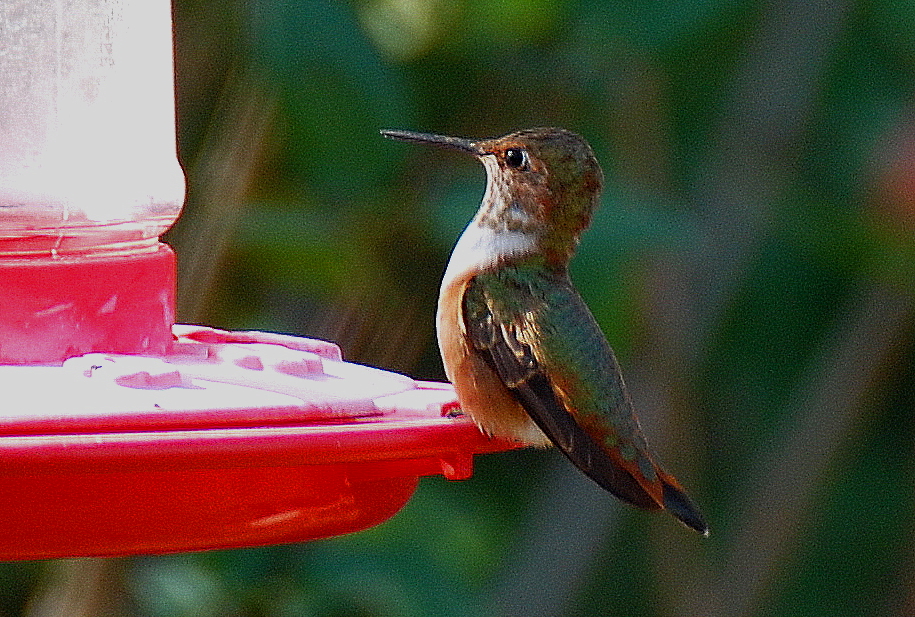

That’s right, I said winter hummingbird. During our second hummingbird season, which extends from November through March, a small number of western hummingbirds winter in Georgia. By far, the hummer that winters here most often is the rufous hummingbird. However, it appears that our chances of spotting one of these little brown hummers feeding at our feeders on a winter day may be tumbling down like a snowflake falling from the winter sky.

The reason for this is that the rufous hummingbird population is declining.

The release in October of “2022 U.S. State of the Birds” has sent shockwaves through the birding community. According to findings published in the report, the U.S. and Canada have lost 3 billion birds that breed in those countries in the past 50 years. Populations are lower for more than half of the bird species that live in the U.S.

When I read the report the thing that surprised the most was the rufous hummingbird is one of 70 species whose numbers have dropped by at least 50 percent in the past half-century. Currently, the population of this hummer species is declining roughly 2 percent a year. In addition, if this trend continues, it will plummet another 50 percent during this next 50 years.

Fortunately, the population of our beloved ruby-throated hummingbird has increased by a whopping 17 percent from 2004-2019.

The rufous hummingbird nests farther north than any other hummingbird that breeds in North America. This tiny long-distance migrant principally nests in Washington and Oregon, and in Canada’s western provinces all the way to southeastern Alaska. The birds winter from north-central Mexico south to Costa Rica.

Rufous hummingbirds hold the distinction of making one of the longest migrations of any bird in the world as measured by body length. Measuring roughly 3 inches long, a rufous that nests in Alaska would have to fly 3,900 miles one-way to reach its winter home in Central America. This distance converts into nearly 78.5 million times the length of its body.

One reason I have such a keen interest in this species is that over at least the past three decades the rufous hummingbird has become a more common winter resident throughout Georgia. During that time, rufous hummingbirds have been showing up in growing numbers throughout the state and the rest of the Southeast.

I spotted my first rufous hummingbird while working out of my former office on Rum Creek Wildlife Management Area in Monroe County. On an October day in 1988, while talking on the phone with a fellow biologist in south Georgia, I was startled to see a rufous visiting a hummingbird feeder hung outside my office window. The bird stayed for three days before departing for points unknown. At the time I saw that bird, there had been only three verified reports of rufous hummingbirds in the state. Interestingly, rufous hummingbirds were seen in Monroe County each year from 1988-90.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, the numbers of sightings of rufous hummingbirds in Georgia exploded. I suspect this was due to a number of factors. For example, it is entirely possible that more rufous hummingbirds were wintering in Georgia than we realized. It is interesting to note that sightings also rose throughout the Southeast during this time. Then again, the pioneer banding and education efforts of Nancy Newfield in Louisiana and Alabama’s Bob and Martha Sargent also were making more people aware of wintering hummingbirds. And Georgia hummingbird fancier Buddy Rowe launched an organization called Georgia Hummers. His tireless efforts also fostered interest in wintering hummers.

I also believe that Georgia DNR’s then-fledgling Nongame-Endangered Wildlife Program played a key role in nurturing interest in all things hummingbird in Georgia. In 1989, the program – now known as the Wildlife Conservation Section – launched the highly popular Hummingbird Helper Project, which urged homeowners to enhance their yards with nectar plants to benefit hummingbirds. The agency also encouraged Georgians to maintain least one hummingbird feeder at their homes throughout the winter, and to report all wintering hummingbirds. This was done after the project revealed that, at that time, 57 percent of homeowners who fed hummingbirds took their feeders down in October.

The winter following the call for people to report wintering hummingbirds, sightings from St. Simons Island to Rabun Gap began pouring in. In 1993, the program received 40 winter hummingbird reports. In 1995, that number swelled to more than 200, the vast majority of which proved to be rufous hummingbirds. Most of the 1995 reports came from the Atlanta area.

It is ironic that at the very time when more Georgians are hosting rufous hummingbirds than ever before, the chances of that may be dwindling.

A number of theories have surface to try to explain the bird’s precipitous decline. Those include global warming, pollution and increased habitat loss and degradation in the bird’s breeding, stopover and wintering grounds. Canadian researchers are focusing on the possibility that the proliferation of insecticides known as neonicotinoids are a factor. These chemicals are absorbed by plants and subsequently move into the plants’ tissues and even their nectar. To determine neonicotinoid levels in birds, scientists are analyzing urine and fecal samples collected during bird banding operations. In addition to this, other biologists have launched studies designed to fill the considerable gaps in what is known about the life history of rufous hummingbirds.

I know you share my hope that these efforts will prove successful in identifying what’s behind the species’ decline. In the meantime, if you have never hosted a wintering rufous hummingbird, why not try to do so this winter? One caution is that it may take a while before your efforts are rewarded. Eighteen winters passed before my wife and I spotted the first rufous at our feeders. But then they visited for the next five years.

Attracting a wintering rufous is like playing the lottery. Chances are you will never win. However, there is always a chance you will look out of a window one winter day and see the bird you’re hoping for. It will be a moment you will always remember. Even if you don’t see one of these magical hummers, just knowing you have a chance of seeing one adds an exciting new dimension to your backyard birding.

I am glad my wife and I have been lucky enough to have hosted rufous hummingbirds. Although we have not seen one for a number of years, each winter we still maintain hummingbird feeders throughout winter in hopes that we will be lucky enough to see one again.

Maybe it would improve our luck if I started carrying a buckeye in my pocket. But let’s see, if I want to have good luck, do I carry it in my left or right pocket?

Terry W. Johnson is a retired Nongame program manager with the Wildlife Resources Division and executive director of The Environmental Resources Network, or TERN, friends group of the division’s Nongame Conservation Section. (Permission is required to reprint this column.) Learn more about TERN, see previous “Out My Backdoor” columns, read Terry’s Backyard Wildlife Connection blog and check out his latest book, “A Journey of Discovery: Monroe County Outdoors.”