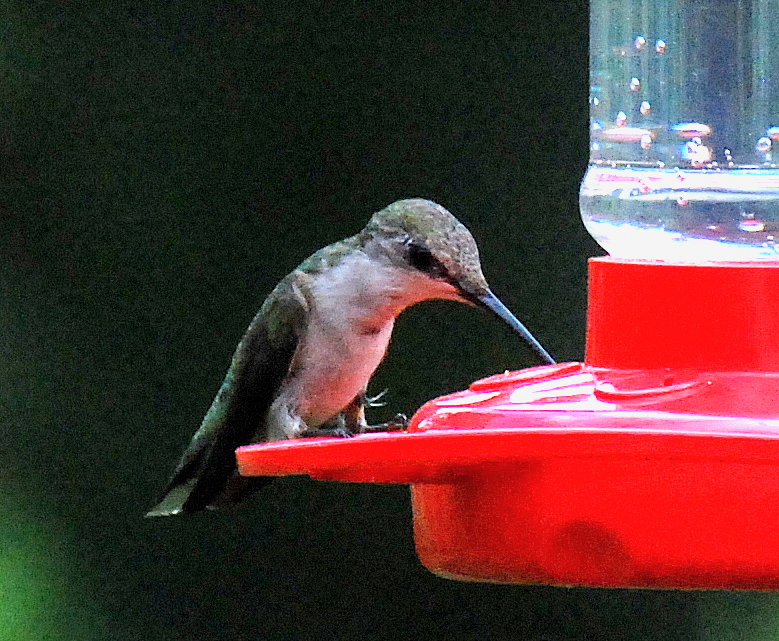

Ruby-throated hummingbird at feeder in August by Terry W. Johnson

Before I retreated to the pleasant temperatures in my home office to write this column, I was standing on my deck of my middle Georgia home watching a squadron of hungry hummingbirds circling two feeders hanging from a shepherd’s hook. Since the air temperature was 95 degrees Fahrenheit and the heat index (feels-like temperature) was a Sahara desert-like 115, sweat was dripping from my brow. The torrid, unrelenting summer heat was also heating the sugar water in the nearby feeders.

When it is this hot, hummingbird fans across Georgia and much of the rest of the nation are beginning to wonder if the “hot” nectar in their feeders might be harmful to the beautiful birds they are trying to help.

Not too long ago this potential threat caught the attention of the scientific community. Consequently, researchers are now directing trying to determine whether the sugar water in hummingbird feeders can become so warm it poses a threat to hummingbirds. In one study, biologists learned that when hummingbirds were fed nectar heated to 102.2 F, the metabolic rate of the birds feeding on the liquid rose to the level where it could harm their delicate metabolic system. Nectar this hot is also purported to cause a burning sensation on the birds’ tongue.

If that is the case, you are probably wondering what is considered the best temperature for nectar offered to hummingbirds. The answer is 100 degrees F. This is because the lower the temperature of the nectar, the more energy is required for the hummingbird to raise the liquid’s temperature to a point where the bird’s body can optimize use of the food. However, I do not know of any studies demonstrating that lower nectar temperatures in backyard feeders pose a potential threat to hummingbirds.

Meanwhile, some hummingbird enthusiasts are already trying to address this issue. For example, some are using only feeders that are equipped with glass reservoirs. The reason for this is glass is an excellent insulator. Consequently, on a summer day, sugar water held in glass feeders should be cooler than nectar housed in plastic feeders. Others are wrapping the reservoirs that contain hummingbird food with aluminum foil. The idea is the aluminum foil reflects the sun’s ultraviolet rays as well as 98 percent of the radiant energy striking the protective covering.

Of course, another way to address overheating is to hang feeders in the shade.

Now let’s look at what we do know. Most hummingbird fans realize that nectar does not spoil as quickly in feeders placed in the shade as it does in the sun. The food in feeders hanging in bright sunshine during the abnormally hot temperatures we are experiencing this year is becoming contaminated with mold and bacteria more quickly than during a normal year.

Four of the diseases that hummingbirds can contract eating food infected with mold and bacteria are aspergillosis, candidiasis, avian poxvirus and salmonellosis. These organisms can adversely affect the birds in many ways, including attacking their beaks and tongues and causing gastrointestinal problems.

Years ago a woman told me that she could tell when the nectar in her feeders had gone bad by simply tasting it every day. According to her, she knew the nectar needed to be changed when it tasted bitter. I must confess that I have never tried her method. Instead, I look at the clarity of the nectar. If the nectar is cloudy, it needs to be immediately poured out and the feeder cleaned. Some enthusiasts don’t take a chance with contaminated nectar: When the temperature tops 90, they change the nectar every two to three days.

Another way to prevent hummingbirds getting sick from dining at your feeding station is to reduce the amount of food you put out for the birds. For example, if the hummingbirds visiting your feeder do not devour all of the food in your feeder each day, reduce the amount offered. Although this may require refilling your feeder more often, it reduces the chance of the nectar becoming contaminated while also cutting down on the amount of sugar water that has to be thrown away.

Although feeding hummingbirds this summer may be more challenging than ever, I think we all agree that the tiny flying jewels that bring us so much joy deserve a dependable, abundant source of clean, fresh and cool food. It is up to each of one of us to determine the best way we can accomplish this goal.

Terry W. Johnson is a retired Nongame program manager with the Wildlife Resources Division and executive director of The Environmental Resources Network, or TERN, friends group of the division’s Nongame Conservation Section. (Permission is required to reprint this column.) Learn more about TERN, see previous “Out My Backdoor” columns, read Terry’s Backyard Wildlife Connection blog and check out his latest book, “A Journey of Discovery: Monroe County Outdoors.”